ANNUAL EMPHASIS. . . .

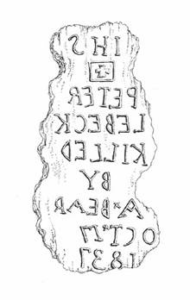

This year the Ridge Route Communities Museum is commemorating the 175 th anniversary of the first recorded non-Indian burial in our mountain area. It seems that back in 1837, Peter Lebeck was in these mountains with a number of companions when he was involved in a fatal confrontation with a grizzly bear. Those traveling with Mr. Lebeck must have thought highly of him because they took the time to bury his mangled body below one of the huge oak trees in the future area of Fort Tejon , and to carve a substantial epitaph in the same tree.

Through the years that followed that location, with its fresh flowing stream, became a popular travelers and teamsters rest stop along the roadway that had developed through these mountains. The skulls of many grizzlies were found there and Indians told of the man who was killed by one of them. Several journals recorded the carving on the tree until the noble oak repaired itself and covered the scar with new bark.

Over fifty years later, in 1889, a group of summertime campers made their annual trek to the site of old Fort Tejon to escape the heat of Bakersfield . One of the adventurers noticed a split in the bark of the old oak tree and when reaching in felt letters on the backside of the bark. When the bark was carefully removed a relief of the original carving was found even though the tree itself had been healed of the carving.

(Illustrated by Susan Sjoberg )

By the time the campers returned to Bakersfield they had a plan to get permission from the owners of the property to prove up the epitaph. Permission granted, the group returned the next summer and after much discussion and planning began the task of opening the grave so long sealed.

Several feet down, bones were discovered which proved the burial. With dirt carefully removed the entire frame was exposed. The left arm was folded across the chest, the right forearm was missing as were both feet and the left hand. It was determined that two ribs on the right side were broken and that the skeleton was nearly six feet long and “broad in proportions”.

After several photographs were taken, the surrounding earth was carefully worked over by hand in the hopes that something of a metallic nature, that even a button could be found, but there was nothing suggesting the man was probably buried in buckskins. Following the crude research, the grave was once again closed from human sight and the ladies of the group covered the mound with flowers. The crude research of this group of adventurers has benefited the generations to follow and Peter Lebeck’s name continues on in the town named after him.